By América Torres

Many professions carry the risk of developing pulmonary diseases. The lungs are organs with an extensive surface area, high vascularity, and a thin barrier between air and blood. This structure makes them a contact site for environmental agents, many of which have local and/or systemic or immunological toxic effects. Exposures to toxic substances can cause virtually all major clinical forms of respiratory illness, implying that many lung diseases may have an environmental or occupational cause.

For these reasons, it is recommended that pulmonologists consider a differential diagnosis for every major pattern of respiratory illness, including both occupational and environmental exposures. In this article, we discuss the need to evaluate individuals proactively and early at occupational risks to prevent their lung health from deteriorating over time.

Evaluating the risk of occupational lung diseases

Evaluating the risk of occupational lung diseases

In order to diagnose occupational lung diseases, it is useful for the physician to obtain a comprehensive work history of the patient. Preferably, this should include all occupations the patient has held throughout his professional life, mentioning any associated exposure to chemicals, biological products, vapors, gases, dust, and/or fumes. If possible, it is helpful for the patient to provide information about the approximate intensity and duration of these exposures.

Diagnosing the occupational cause of a lung disease is a very serious matter for several reasons:

- It can influence the treatment and prognosis of the disease.

- It can have legal implications for the company.

- It may entail professional decisions and financial implications for the patient.

- It can help identify a larger population at risk.

- It can contribute to research on a certain type of disease.

Physicians need to assess the probable exposure dose as best as possible (in terms of duration, measured levels, and subjective intensity). The latter can determine the severity of the disease in an affected individual, the incidence of the disease among other workers exposed to certain conditions, or the speed of onset, but not necessarily all three.

While it is true that occupational lung diseases are preventable, as exposure elimination will lead to future disease elimination, many chronic diseases, particularly interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), once established, can progress despite reducing exposure to the offending agent. However, it is important to note that, similar to tobacco smoke, not all individuals occupationally exposed will develop the disease, and susceptibility may be determined by factors that are often unclear.

Below, we will briefly discuss some lung diseases that can develop due to occupational exposure to pathogenic agents.

Occupational asthma

Occupational asthma

There are two main types of work-related asthma. Occupational asthma (OA) is caused by airborne exposures in the working environment, while in work-exacerbated asthma, a variety of nonspecific factors in the workplace can worsen asthma symptoms, but the asthma is not caused by work. The characteristics of these two conditions are not easily distinguishable from each other. Work-exacerbated asthma is common and is estimated to affect one fifth of asthmatic patients.

Work-related asthma is common but is often under-recognized for several reasons. Firstly, the patient may not relate asthma symptoms to their work. Secondly, the physician may not think to inquire specifically about any work-related symptoms, therefore may not consider it necessary to assess work-related asthma in the patient. Additionally, there is limited information in international asthma guidelines about OA and its causes.

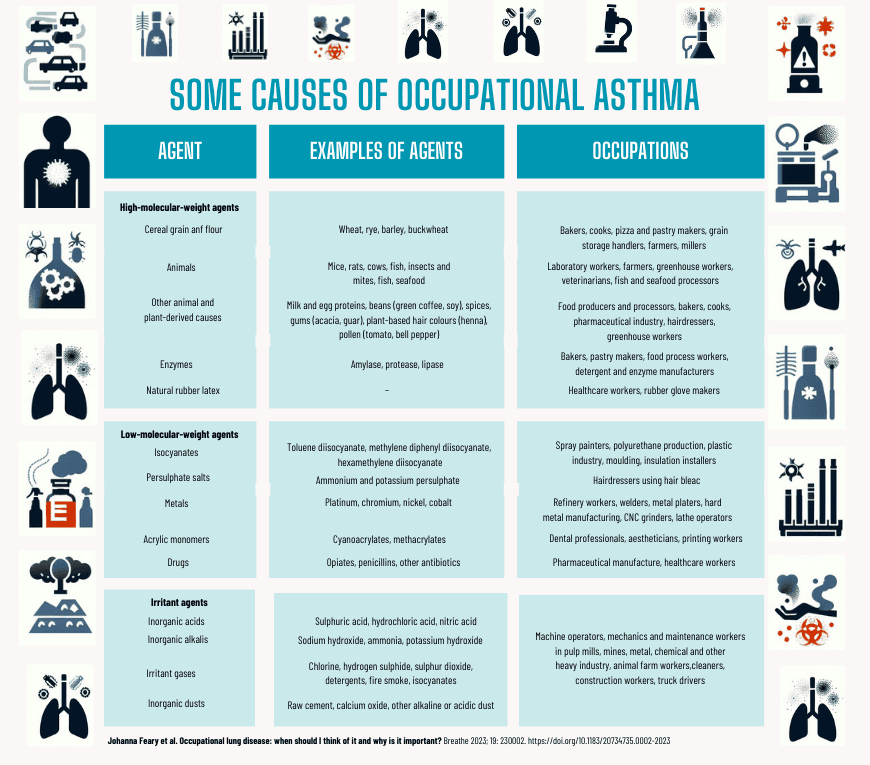

The table to the right shows some of the most common causes of occupational asthma:

Occupational COPD

Occupational COPD

The primary causative agent of COPD is the inhalation of tobacco smoke, as it provides the lungs with a powerful and complex mixture of respiratory toxic substances. While pulmonologists are aware of this association, research has shown that there is a considerable proportion of COPD patients (25-35%) who had never smoked. It is also known that there are exposures and risk factors for the development of the disease, which in many cases can act in conjunction with cigarette smoke.

Over time, various landmark publications established the role of occupational exposures to dust, gases, and fumes in the development of "focal emphysema," COPD, and industrial (non-obstructive chronic) bronchitis, respectively. In 2019, a joint statement from the ATS (American Thoracic Society) and the ERS (European Respiratory Society) estimated the smoking-adjusted population attributable fraction (PAF; i.e., the proportional reduction in COPD in the population that would result from exposure elimination) for the occupational contribution to COPD at 14% (95% CI 10-18%) and 31% (95% CI 18-43%) when studies are restricted to non-smokers. For chronic bronchitis, the PAF was 13% (95% CI 6-21%).

In addition to occupational exposures, research has identified the role of environmental exposures (such as indoor air pollution from biomass burning, secondhand smoke, or outdoor air pollution). Furthermore, genetic susceptibility factors, factors or events affecting lung development in early life, including dysanapsis (disproportion of airway dimensions in relation to lung alveoli), accelerated aging, or lung diseases throughout life, such as asthma (especially in individuals with occupational asthma), tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, HIV, and other viral and non-viral infections, must be considered.

Agents with solid evidence of association with COPD include coal mine dust, silica, grains, and textiles. Evidence is weaker in cases of exposure to agricultural dusts, asbestos, cadmium, carbon black, refractory ceramic fibers, endotoxin, flour, isocyanates, welding fumes, coke oven emissions, diesel exhaust, and tunnel dust and fumes.

Occupational interstitial lung diseases

Occupational interstitial lung diseases

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) manifest through variable combinations of parenchymal inflammation and/or fibrosis. There are some inhalation exposures encountered in the workplace that are well-established causes of ILD, where both exposure and disease are easily identified. For example, exposure to coal dust and pneumoconiosis.

However, in other ILDs, the association between occupational exposures and disease may not be evident, especially if the clinical or radiological picture of the patient is nonspecific. This can result in patients experiencing symptoms without an identified etiology and, therefore, without appropriate clinical management and advice regarding the health risk posed by their employment.

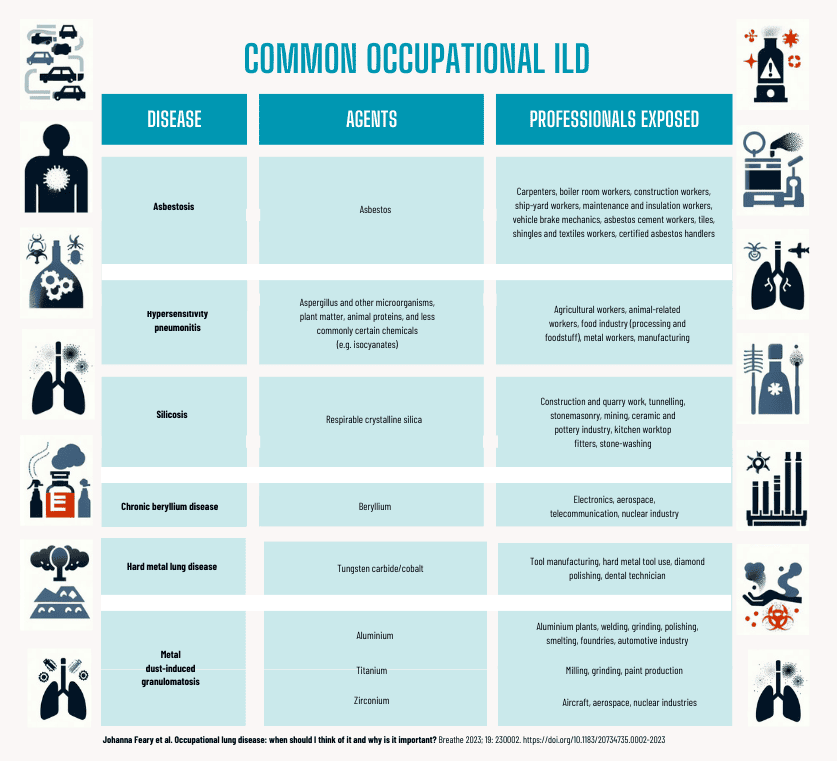

The table to the left shows the agents responsible for the most common interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) and the professionals who suffer exposure to these agents.

Spirometry and oscillometry: two valuable tools for comprehensive assessment

Spirometry and oscillometry: two valuable tools for comprehensive assessment

As we have seen, there are many cases where it is not clear whether the patients' lung disease is due to occupational reasons. This is especially common in those cases where there is not solid evidence that exposure to certain agents is the cause. Therefore, it is necessary for doctors, starting with primary care physicians and up to pulmonology specialists, to have tools that help them obtain an accurate and, above all, timely diagnosis. This latter point, which is always so important, becomes urgent in the case of occupational diseases, as treatment often involves the patient changing professions to prevent or avoid the condition from worsening rapidly.

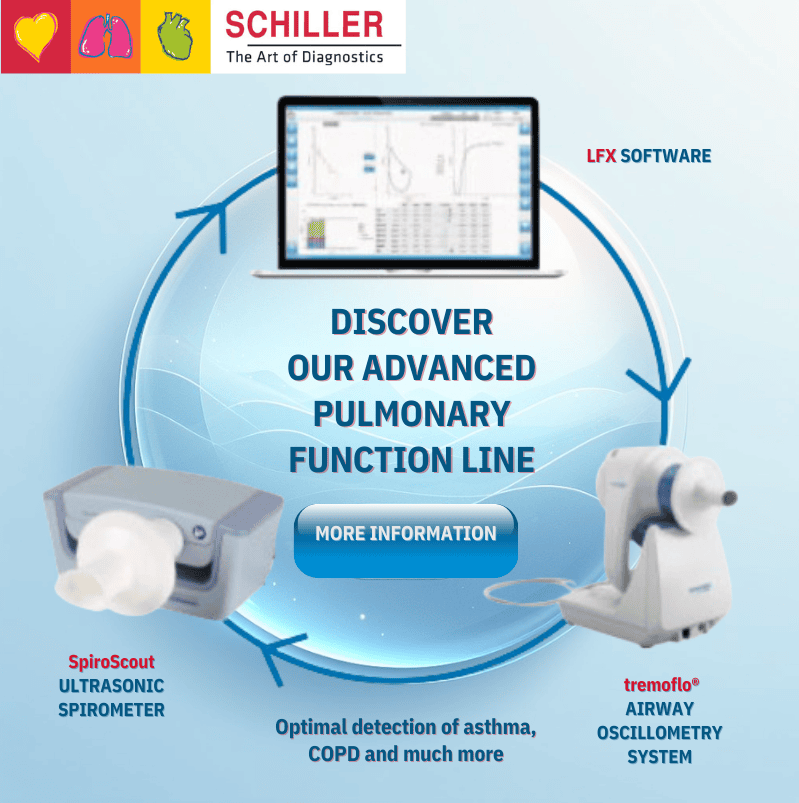

• Spirometry (with the Ultrasonic Spirometer, SpiroScout) allows for the measurement of lung flows and volumes but does not provide information on how these flows and volumes are moving.

• Oscillometry (with the tremoflo® Airwave Oscillometry System) provides information about the resistance present in the airways but does not provide data about the amount of air moving in the lungs.If the physician only performs one of these tests, they receive useful information, but they only see half of the picture. To have complete information about the true lung status of the patient, they need to know how much air enters their lungs and the level of resistance present. Therefore, spirometry and oscillometry are complementary tests.

Contact us to get more information or request a no-obligation demonstration. Discover the advanced technology of our ultrasonic spirometer, SpiroScout, and the tremoflo® oscillometer. Click the button below.

REFERENCE

Johanna Feary et al. Occupational lung disease: when should I think of it and why is it important? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10292794/pdf/EDU-0002-2023.pdf