By América Torres

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a heightened risk in older individuals due to physiological changes associated with aging. In older adults, increased atherosclerotic plaque, combined with the complexity of anatomical disease and age-related cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities, contribute to a worse prognosis. Geriatric syndromes such as frailty, multimorbidity, cognitive and physical impairment, polypharmacy, and other complexities of care for these patients can undermine the therapeutic efficacy of guideline-based treatments and the survival and recovery capacity of older adults.

That is why the American Heart Association (AHA) issued the document titled "Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome in the Older Adult Population: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association," which provides various recommendations for managing this issue. The document emphasizes the need for individualized risk assessment and the importance of considering patient preferences in treatment decisions. In this blog, we summarize some of the most relevant aspects of the AHA recommendations for clinical practice in this syndrome.

Cardiovascular Aging

Cardiovascular Aging

Considerations for Clinical Practice

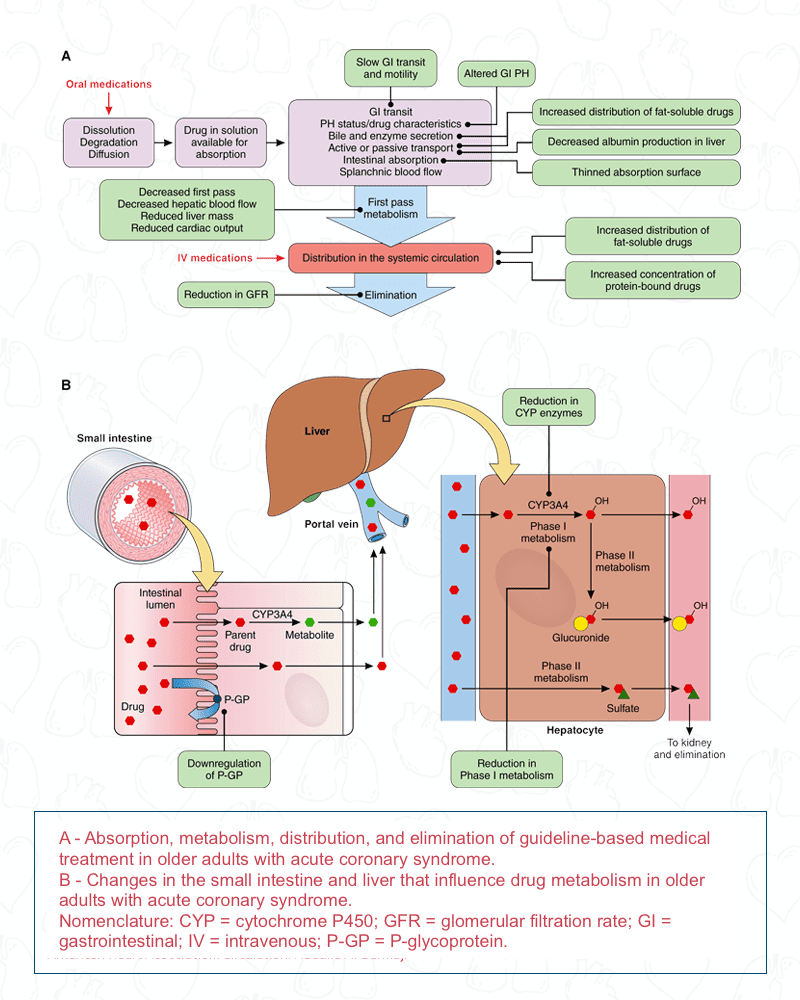

Understanding the pathophysiological changes derived from the process of cardiovascular aging and the aging kidney is crucial for evaluating guideline-based medical treatment for acute coronary syndrome. It is also important for managing age-related risks in order to prevent physical, cognitive, or functional decline in older individuals.

Geriatric Syndromes

Geriatric Syndromes

Considerations for Clinical Practice

Geriatric syndromes can influence outcomes in older patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Conversely, ACS can also worsen the burden of preexisting geriatric syndromes. Therefore, a comprehensive approach proportional to the relatively more complex issues related to ACS in older adults is suggested, along with an individualized and patient-centered approach that considers overlapping and coexisting areas of healthcare.

Diagnostic Classification Based on Acute Coronary Syndrome in Older Adults

Diagnostic Classification Based on Acute Coronary Syndrome in Older Adults

Considerations for Clinical Practice

• Symptoms of acute coronary syndrome without chest pain, such as shortness of breath, syncope, or sudden confusion, are more common in older adults.

• High-sensitivity troponin (hs-cTn) testing is the standard for identifying acute and chronic myocardial injury.

• Myocardial injury can be classified into 4 subtypes: acute non-ischemic injury, chronic myocardial injury, myocardial infarction (type 1), and myocardial infarction (type 2). All of these are more common in older adults than in younger adults.

Pharmacological Therapy Based on Guidelines for ACS in Older Adults

Pharmacological Therapy Based on Guidelines for ACS in Older Adults

Considerations for Clinical Practice

• The preferred antiplatelet therapy for older adults with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is clopidogrel. For patients with STEMI or complex anatomy, the use of ticagrelor is considered more reasonable.

• In patients with chronic atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for ACS, should be minimized the duration of triple therapy. It is advised to discontinue aspirin and transition to dual antithrombotic therapy with clopidogrel and a novel oral anticoagulant, ideally within 4 weeks after PCI.

• It is considered best to evaluate therapies initiated in the hospital during outpatient follow-up, with treatment escalation as necessary to reduce cardiovascular risk. Additionally, the reduction or withdrawal of medications to alleviate or prevent side effects should also be considered.

• Older adults, especially those with mobility or cognitive difficulties, may benefit from relatively simpler medication regimens and dosing than those commonly indicated by existing guidelines.

The following image illustrates the physiological changes that affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of medications used in older adults with acute coronary syndrome [1].

Percutaneous revascularization

Percutaneous revascularization

The management of STEMI in older adults follows the same general principles as for younger patients.

For older patients with NSTEMI (NSTEMI) cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular risk assessment prior to revascularization is critical to achieving optimal outcomes.

Geriatric and Patient-Centered Outcomes for Older Populations with Acute Coronary Syndrome

Geriatric and Patient-Centered Outcomes for Older Populations with Acute Coronary Syndrome

In patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), particularly in older populations, the goals of care should encompass patient-aligned objectives and preferences to maximize their quality of life.

For patients approaching the end of life, treatment objectives include "days spent at home in the last 6 months of life" and relief of pain and discomfort.

Conclusion

The management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in older adults is more delicate due to their anatomical complexity, physiological vulnerability, age-related risks, and heterogeneity in life expectancy and care goals. In this scientific statement, the AHA proposes a framework for integrating geriatric risks into the management of ACS, including a diagnostic approach, pharmacotherapy, revascularization strategies, prevention of adverse events, and transition care planning. Additionally, it emphasizes that post-myocardial infarction care should include individualized cardiac rehabilitation.

REFERENCE

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001112

[1] Damluji AA, Forman DE, Wang TY, Chikwe J, Kunadian V, Rich MW, Young BA, Page RL 2nd, DeVon HA, Alexander KP; on behalf of the American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Older Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; and Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Management of acute coronary syndrome in the older adult population: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147: e32–e62. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001112

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000741